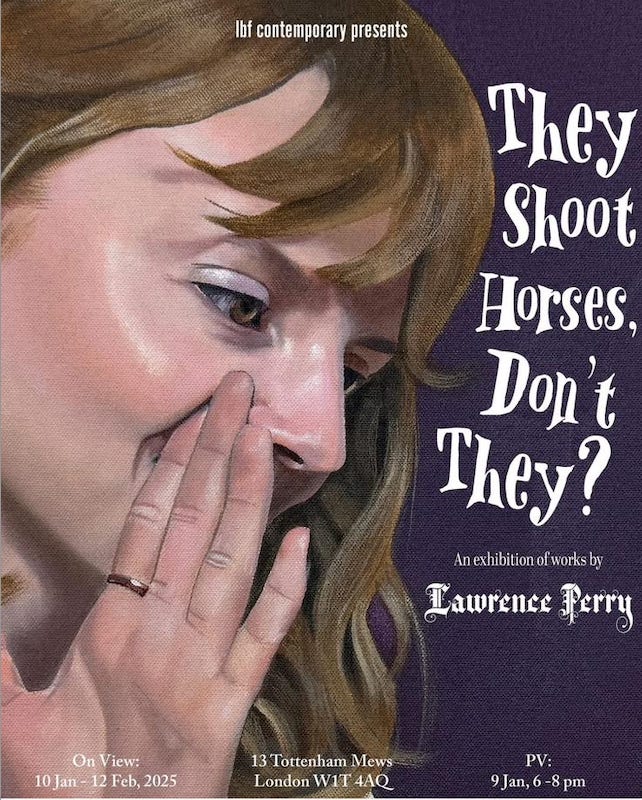

Lawrence Perry: They Shoot Horses, Don't They?

When your favorite living artist is also your son

My eldest son Lawrence is a beautiful, playful, searching soul. At 25, he is also my favorite living artist, with a relentless work ethic, which means that every year or so, he gives birth to a fresh room full of impossible ideas and delicious color.

Stepping into a packed London gallery last week, the sheer courage and joyfulness of it all overwhelms me: where does it come from, and where, over the next half century, might it go?

Even though he perfectly embodies the spirit of ‘Like a Bird’, promiscuously stealing ideas like a magpie, and soaring free with creative lightness, I’ve never dared write about Lawrence’s work. First, I have no idea how to write about art. Second, it’s impossible to put even an inch of distance between my thoughts as a critical observer and my feelings as a parent.

The dilemma: how to share my love for his new exhibition, ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’ when I can’t write a word? Fortunately, this time I don’t have to, because the British art scholar and critic Matthew Holman has written a fascinating essay about it: ‘A Handful of Cherries, A Blade to the Neck’. I will steal shamelessly (shamefully?). I hope you’ll agree, Holman’s insights serve as the perfect guide to each of the eight paintings.

Let’s begin with the smallest, simplest piece ‘Character is Fate’ (all works 2024) with Holman as our guide:

Lawrence Perry’s painting Character is Fate is a close-up of a young woman’s hands cupping lusciously ripe, blackened cherries, which are laden with symbolism: youth, mortality, growth, lust. One cherry is held, perilously, by the thinnest of stems. We imagine what hides beneath the glossy skin of those cherries and, against ourselves, envision the delicate fingers squeezing them until they burst open, flooding the pristine linen dress with titillating colour.

The title, a riff on Heraclitis’ theory that it is one’s actions and decisions––ultimately, one’s character––which determines one’s future, not those of any external force, is pregnant with meaning. We are given only a cropped perspective, and the picture is disconcertingly ahistorical: while the unadorned linen might suggest medieval nunnery, the red star tattoo on the webbed space between thumb and forefinger is decidedly contemporary.

In this subtle decision, Perry sets the tone for this new body of work that moves, restlessly and ceaselessly, back and forth through history, collecting myths along the way, but always observing the present moment in paint.

The Commedia dell’ Arte (or ‘the comedy of the profession’) was an early form of carnivalesque theatre first staged in Neapolitan piazzas in which masked stock characters––trickster, know-it-all, greedy old man––perform to an agreed script but leave room for improvisation and audience participation. Perry was drawn to these conventions and, in Punch and Judith, splices together the English iteration of the Commedia dell’ Arte in puppetry (‘Punch and Judy’) with the Biblical story of Judith beheading Holofernes, the subject of a celebrated Baroque painting by Artemisia Gentileschi. A further scriptural allusion––the apple, perhaps the forbidden fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, which Adam and Eve eat and thus commit the first sin––is devoured by both figures. The scene, then, hovering on the very precipice of neck-slitting violence, speaks to Barthes’ idea that ‘catastrophe is brought to the point of maximum obviousness… all signs must be excessively clear, but must not let the intention of clarity be seen.’ In other words, we know the violence is imminent because all the characters’ gestures prepare us for it, but why the catastrophe is taking place remains opaque.

Perry’s inventive references are mined from a wide range of sources, whether classical mythology, modernist literature, or kitsch. Leda and the Swan subverts the creepy misogyny of the Greek original (in which the god Zeus, disguised as a swan, seduces Leda, a Spartan queen) and sees a present-day Leda gleefully holding an incapacitated, and perhaps dead, swan by the neck, all illuminated in showbiz lighting. In Perry’s version, Leda is not the victim of bestial subterfuge but a commanding presence who knows we are all watching.

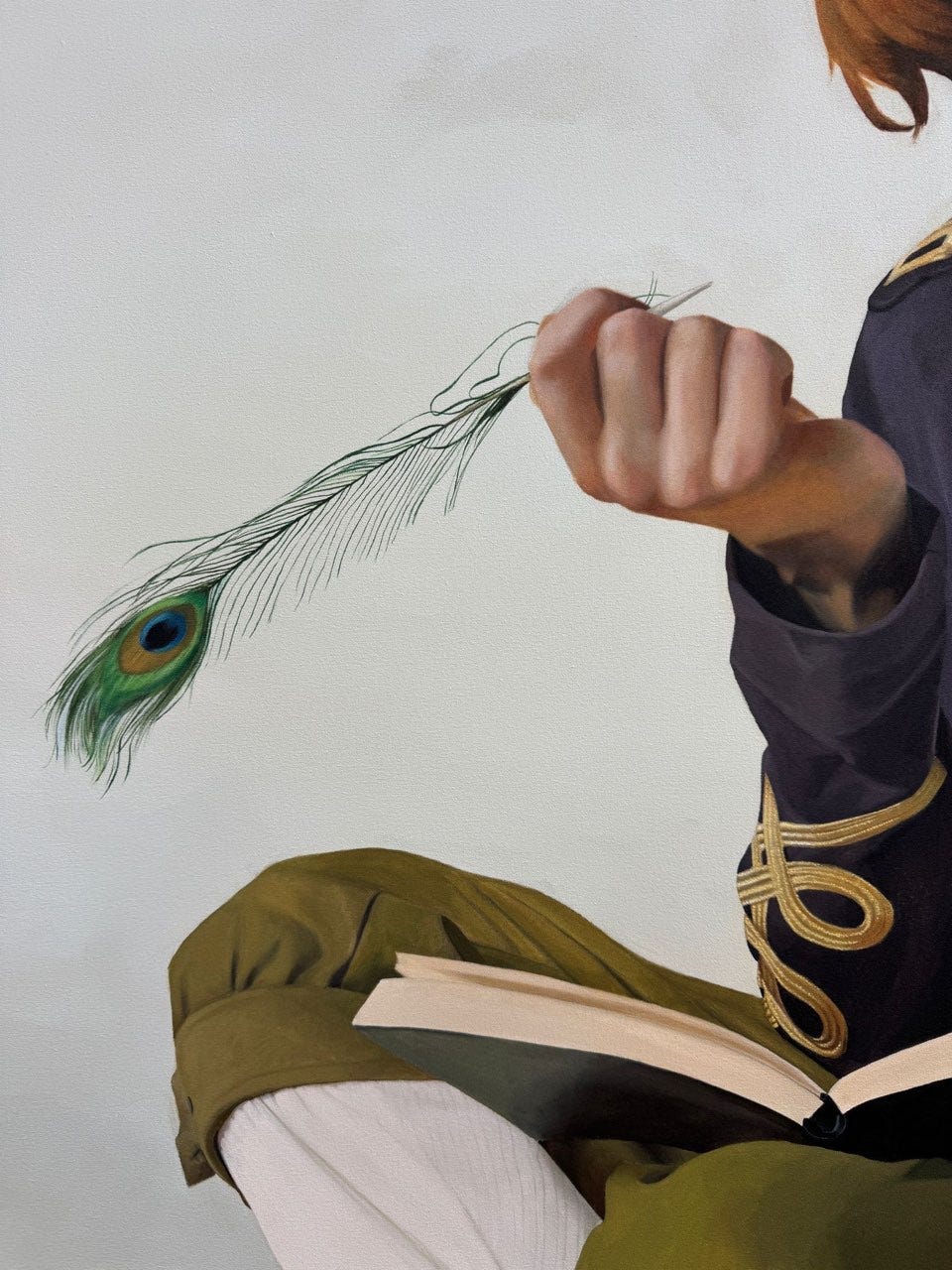

In Orlando the artist depicts Virginia Woolf ’s time-travelling, gender-fluid, age-defying title character––the perfect embodiment of the ‘trickster’ archetype––sat cross-legged on the floor with a quill in his hand, eyes averted skyward.

Other works, like The Ecstasy of Descent, draw explicitly on High Renaissance precedents, such as Caravaggio’s revelatory chiaroscuro paintings and, especially, Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, the sculptural altarpiece in white marble in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. Like Teresa, Perry’s figure––in a stylish emerald-green dress with bow , face flushed red––looks pent up in orgasmic rapture but the withered bouquet loosed from her grip suggests she is ascending not into the throes of divine revelation but descending into a far darker place.

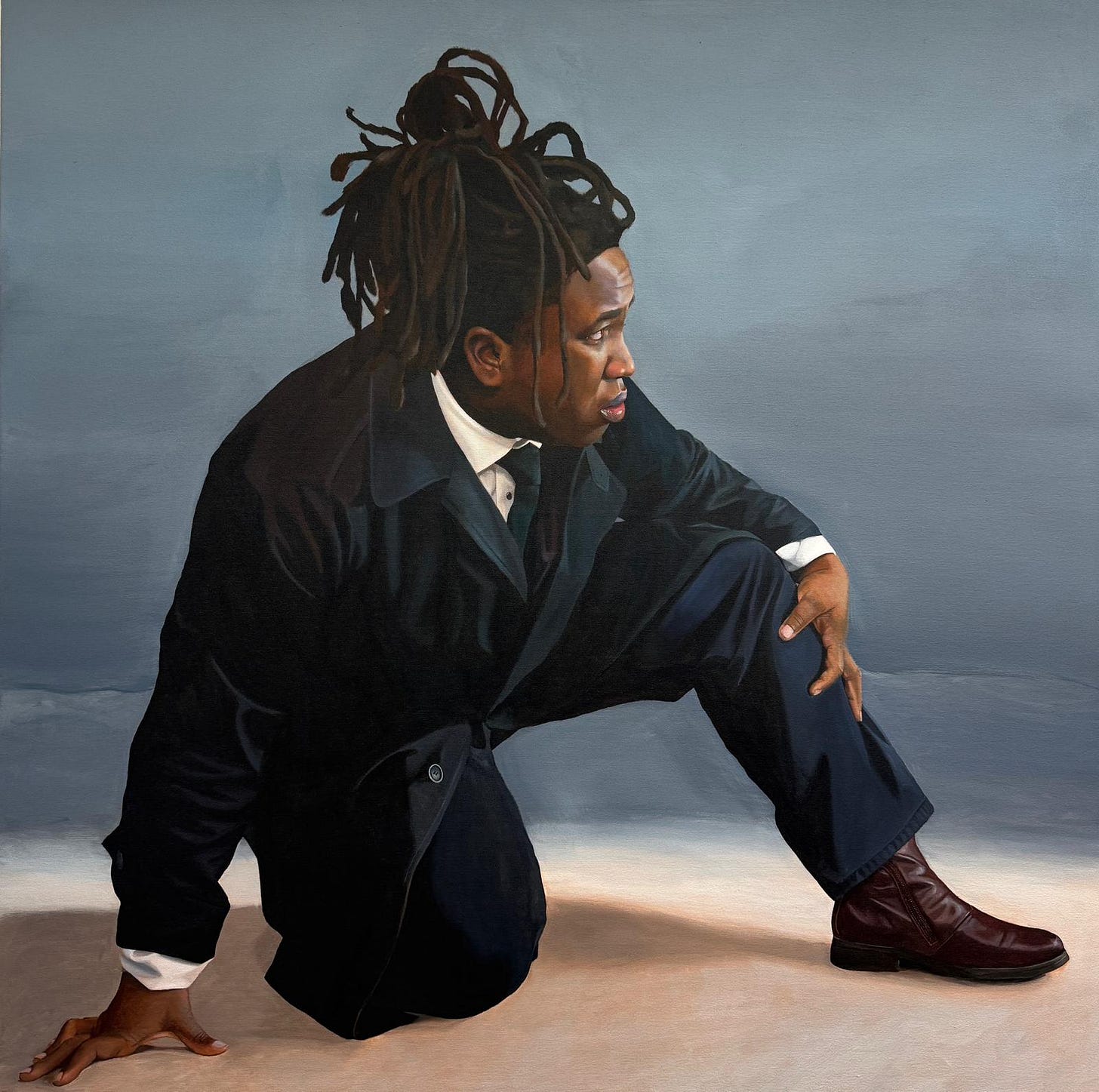

Elsewhere, in Well, Shall We Go?, Perry depicts close friend and fellow artist Shaqúelle Whyte in a stance, with his right knee on the ground and left hand on his left shin, which suggests only a guarded apprehensiveness; he is ready for the threat, unknown to us, which captivates him out of sight. ‘Shaq has these very arachnidian hands’, Perry reflects, ‘which bend in more joints than those of the average person, and so I saw the opportunity to make a portrait where the hands are anxious and contorted giving a sense of anxiety and foreboding, much like Lucian Freud’s Man in a Chair (1983–1985)’. The title, Well, Shall We Go? is lifted from the last scene of Samuel Beckett’s absurdist masterpiece Waiting for Godot (1953): after being bewildered by cruel masters and incalcitrant child messengers, the two protagonists, Vladimir and Estragon, look set to abandon their stay for the absent Godot, perhaps for suicide. This scene is pregnant with an existential doubt which is carried over from play to painting.

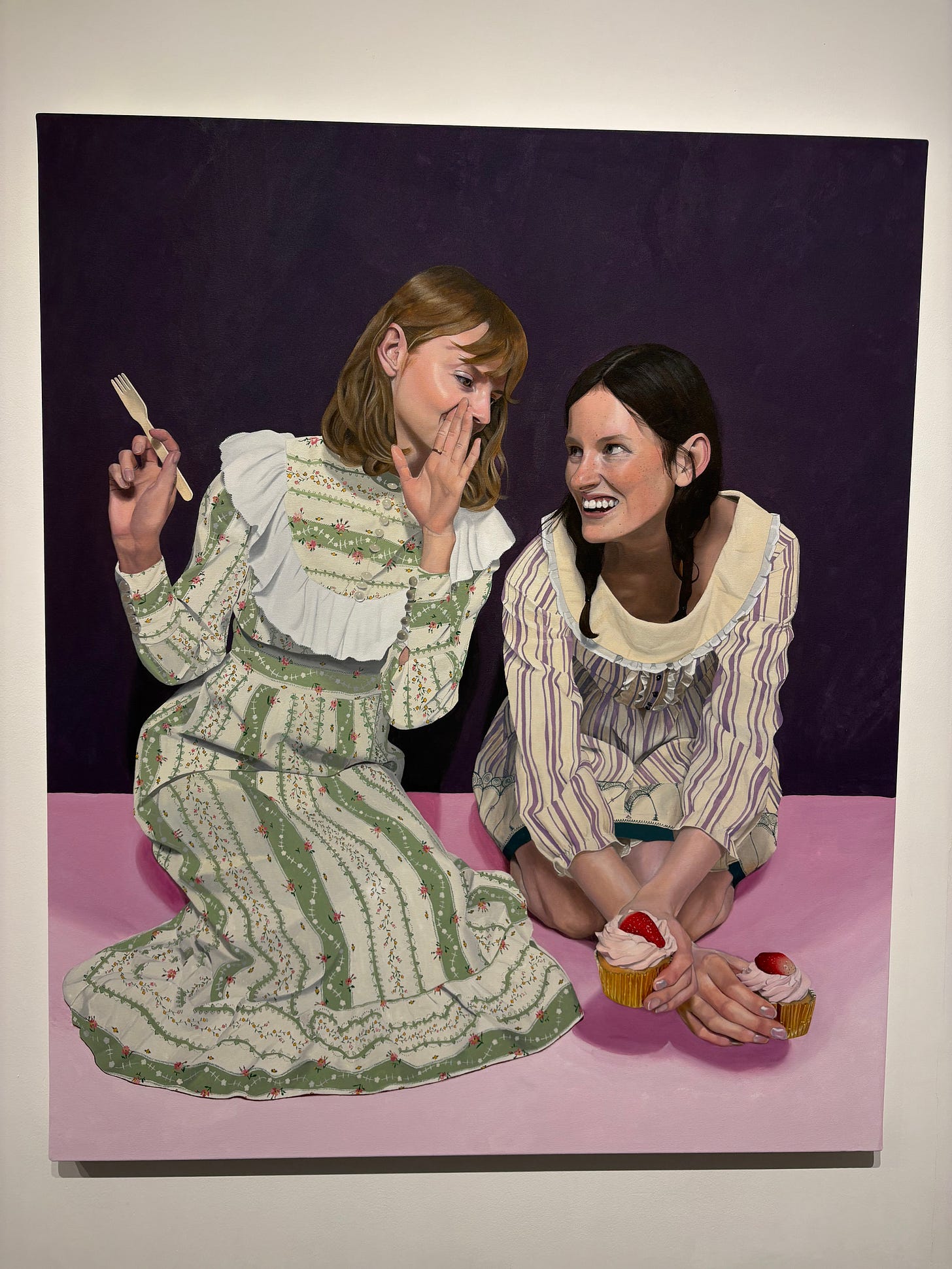

Even the sickly-sweet double portrait of two smirking, whispering young women in Of Chaos and Confection, a theatrical tableau vivant of chic prairie dresses, strawberry cupcakes, and secrets, seems like the premonition of an atrocity. Perry never lets us in on what his characters are saying, muffled behind their gestures; it is probably better kept that way.

…the eponymously titled They Shoot Horses, Don't They? In this extraordinary group portrait seven figures––all modelled on the artist’s intimates, including Whyte, girlfriend Delphi McNicol and fellow artist and friend Orson Campos––are lost in various states of exhaustion, reverie, and ecstasy. Inspired by the marathon dances in provincial American cities during the Great Depression (or ‘bunion derbies’ and ‘corn and callus carnivals’), the giddy jazz-age contests in which couples danced for hundreds of hours non-stop competing for prizes that would keep them above the breadline, Perry depicts a moment when the music stops playing. The picture documents a scene that is at once cruel and caring, exhilarating and etherised, as dance becomes a bout of endurance over an expression of communal joy.

‘All extremes of feeling are allied with madness’, writes Woolf in Orlando. The composition is jolted by the blonde figure in the blue dress and white tights who, in contrast to the couples around her who slump and shimmy, stares back at us with an expression of irredeemable ennui. It is as though, at the very moment that the world around her has lost control, she acknowledges her agency and does not know how to act. Perry’s paintings are animated by what drives us to make decisions, and what holds us back from going through with them. His characters might seem fanciful archetypes from the past but look closer: you will recognise yourself, in our time.

I hope you enjoyed the work and found Holman’s context as insightful as I did. You can follow Lawrence on Instagram at Lawrence.perry_ or at his website lawrenceperry.com.

But if you’re in London before February 12th, 2025, I highly recommend you see the work for yourself, at the LBF Contemporary gallery in Fitzrovia, 13 Tottenham Mews, London W1T 4AQ.

Enjoy!

Your son's art is very striking.

In "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?", I perceive a fourth pairing - the blonde woman (modeled after his girlfriend?) and the painter - each pair being in a different state of relationship.

Absolutely fell in love with his work from this! How stunning